1 引 言

2 北极陆地环境新型有机污染物赋存特征

2.1 OPEs

表1 北极陆地环境与其他典型区域各环境介质中OPEs的浓度比较Table 1 Concentration comparison of OPEs in various environmental media in Arctic terrestrial environments compared with other typical regions |

| 介质 | 北极陆地 | 北极海洋 | 南极 | 其他偏远地区 | 人口密集区 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | |

| 土壤/ (ng/g dw) | 斯瓦尔巴(n=10) | 1.12~44.7[28] | — | — | 菲尔德斯半岛 (n=10) | 0.87~15.7[29] | 喜马拉雅山脉(n=10) | ND~84.80[30] | 世界范围 | 0.1~10 000(中位数范围)[31] |

| 大气/(pg/m3) | 斯瓦尔巴 (n=8) | 340[32-33] | 北大西洋—北冰洋 (n=7) | 363[34] | 菲尔德斯半岛 (n=7) | 57~644(pg/da)[35] | 比利牛斯山脉(n=5) | 5.3~100[36] | 上海 (n=13) | 580[37] |

| 努纳武特 (n=14) | 291[38] | |||||||||

| 水体/ (ng/L) | 哈森湖 (n=14) | 12.2±0.9[23] | 北大西洋—北冰洋 (n=7) | 0.35~8.40(2.94)[34] | 菲尔德斯半岛湖泊(n=11) | 12.23~79.14(19.21)[39] | 比利牛斯山高山湖泊 (n=5) | 0.14~2.85[40] | 世界范围 | 25~3 671[41] |

| 斯瓦尔巴 (n=12) | 6.81~19.3[42] | |||||||||

| 沉积物/ (ng/g dw) | 斯瓦尔巴 (n=12) | 0.01~7.41[42] | 白令海峡—北冰洋中部 (n=7) | 0.16~4.67[43] | — | — | 马里亚纳海沟(n=10) | 422[26] | 中国长江流域 (n=16) | 84.3[35] |

|

2.2 PFASs

表2 北极陆地环境与其他典型区域各环境介质中PFASs的浓度比较Table 2 Concentrations comparison of PFASs in various environmental media in Arctic terrestrial environments compared with other typical regions |

| 介质 | 北极陆地 | 北极海洋 | 南极 | 其他偏远地区 | 人口密集区 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | 地区 | 浓度 | |

| 土壤/(ng/g dw) | 斯瓦尔巴 (n=20) | 0.12~4.84(1.08±1.38)[51] | — | — | 南极(n=32) | 0.198[52] | 纳木错盆地(n=13) | 0.130~1.507[53] | 长江流域(n=26) | 0.991~29.4[54] |

| 加拿大北极群岛(n=16) | 0.20~9.52(1.18)[55] | |||||||||

| 大气/(pg/m3)(中性PFASs) | 努纳武特(n=11) | 28[56] | 日本—北冰洋(n=13) | 61~358[57] | 南极半岛西部(n=10) | 17.3[58] | 阿尔卑斯山(n=3) | <LOD~72.4[59] | 中国 (n=14) | 11~410[60] |

| 格陵兰岛(n=7) | 1.82~32.1[61] | |||||||||

| 水体/(ng/L) | 哈森湖(n=19) | 0.3~10[24] | 格陵兰海—北冰洋(n=29) | 140~850[7] | 菲尔德斯半岛(n=13) | 2.67[62] | 纳木错(n=13) | 0.98~1.28(平均值范围)[63] | 中国呼伦湖(n=30) | 1.21[64] |

| 努纳武特(n=19) | 1.1~2.4[56, 65] | |||||||||

| 加拿大北极机场下游(n=19) | 112~153[65] | |||||||||

| 朗伊尔城(n=17) | 1.5~3.5[66] | |||||||||

| 沉积物/(ng/g dw) | 加拿大北极地区(n=19) | 0.001~0.73[65] | 挪威峡湾(n=1) | 0.14~6.54[67] | — | — | 多伦多湖机场下游(n=8) | 13[68] | 长江 (n=15) | 0.058~0.89[69] |

| 加拿大北极机场下游(n=19) | 11~24[64] | |||||||||

|

2.3 NBFRs

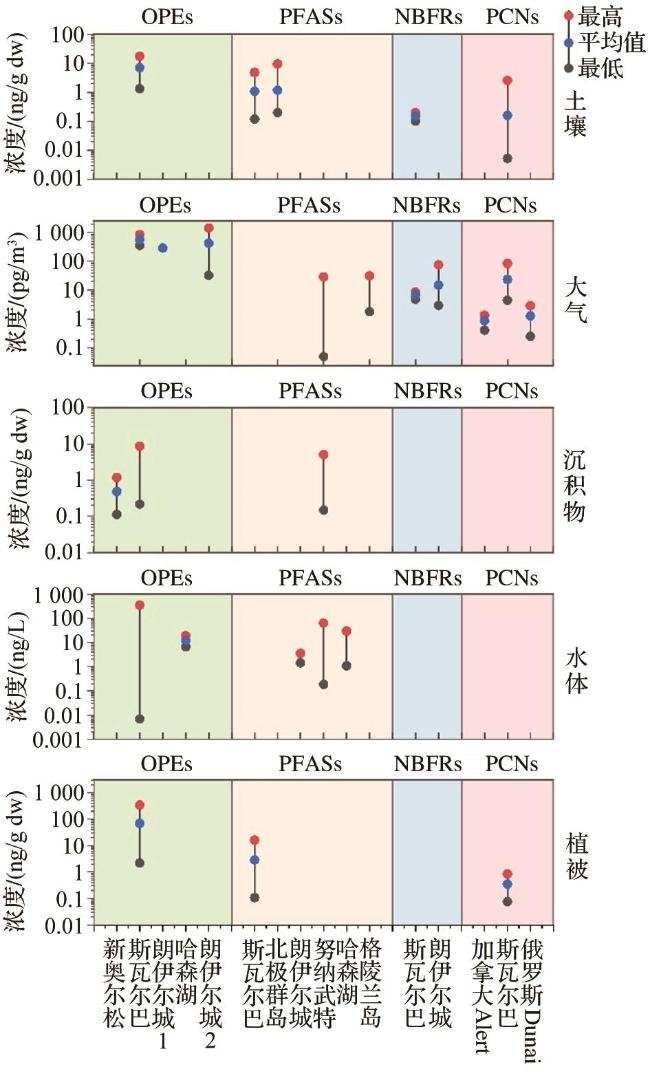

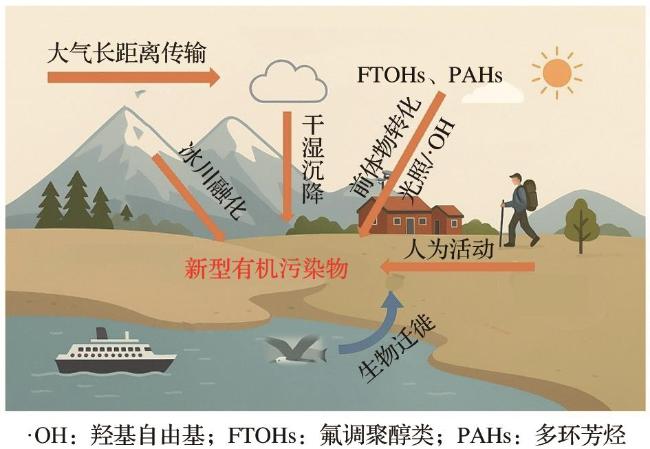

图1 新型有机污染物在北极陆地环境中的浓度水平朗伊尔城1:指该地区大气样品的气相;朗伊尔城2:指该地区大气样品的颗粒相。 Fig. 1 Concentration levels of emerging organic contaminants in Arctic terrestrial environments Longyearbyen 1 refers to the gas phase of atmospheric samples in this region; Longyearbyen 2 refers to the particle phase of atmospheric samples in this region. |

甘公网安备62010202000687

甘公网安备62010202000687